https://inthesetimes.com/article/alienated-labor-capitalism-jobs-work

“We need a politics of time. A political understanding that our lives are ours to do with what we will.”

The “labor-of-love myth” — the idea that certain work is not really “work” and therefore should be done out of passion instead of pay — is cracking.

There are occasional pleasures to be had on the job, certainly; we should take any opportunity for happiness and connection that we get. I do believe, however, that our desire for happiness at work is one that has been constructed for us, and the world that constructed that desire is falling apart around us.

Work itself no longer works. Wages have stagnated for most working people since Reagan and Thatcher’s time. A college degree no longer guarantees a middle-class job. The pandemic exposed the failures of the U.S. healthcare system and the brutality of “essential” work for those who had no choice but to keep going to their jobs despite the heightened danger.

A society where we must work the majority of our waking hours will never deliver us happiness, even if we are the lucky few who have jobs in which we do gain some joy. As feminist activist and scholar Silvia Federici wrote, “Nothing so effectively stifles our lives as the transformation into work of the activities and relations that satisfy our desires.”

Capitalist society has transformed work into love, and love, conversely, into work. But we are beginning to change our minds about our priorities, whether capital likes it or not. Surveys find more people rating “working hours are short, lots of free time” as a characteristic of a desirable job over time, while their desire for “important” work went down. This was true among the highly educated as well as the less educated.

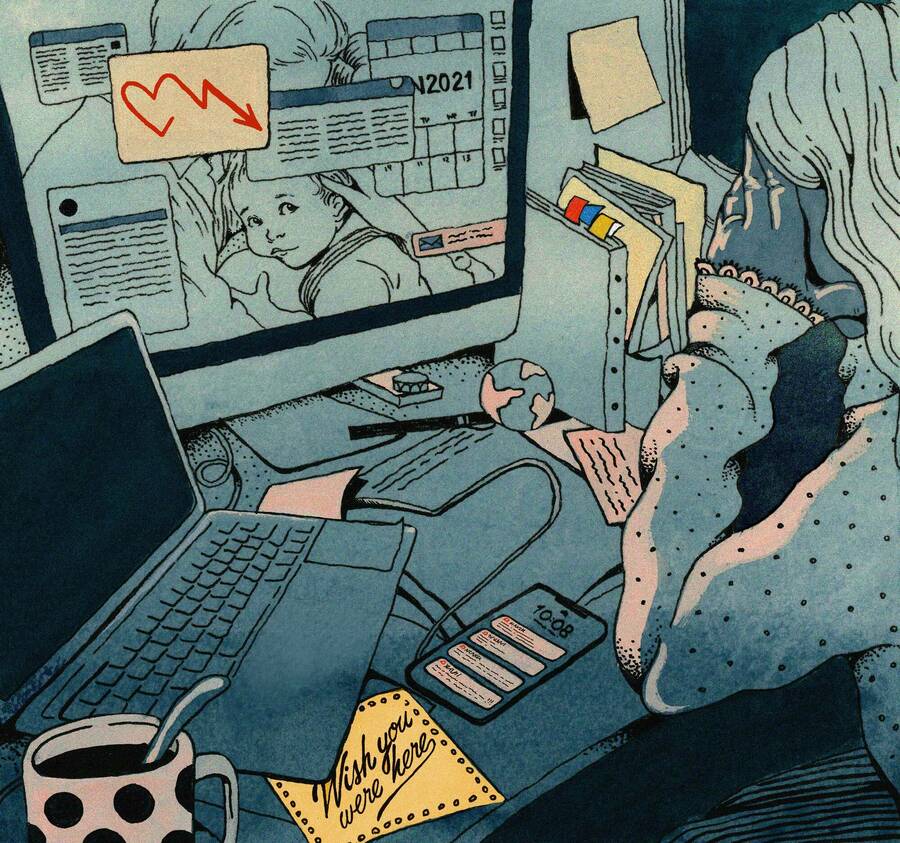

A side effect of all this love for work has been that talking about love between people has lost its importance. Instead, our personal relationships are to be squeezed in around the edges, fitted into busy schedules or sacrificed entirely to the demands of the workplace. Love was understood for a long time to be the opposite of work. Love was for the home, for the family, for the couple; the workplace was where you earned what you needed to sustain that love. Love was also presumed to be more important for women than for men; the home was women’s sphere, the workplace men’s. In reality those lines were always blurred; plenty of women always worked, for one thing, even from the very beginnings of industrial capitalism, and plenty of bosses wanted to extend their control into the home. Henry Ford, for example, famously sent investigators into the homes of his workers to make sure they were upstanding, straight and monogamous, and therefore deserving of higher wages.

As the workplace has changed, our ideas about love have also changed. The feminist revolution known as “the second wave” notably demanded access to career-track work for women, seeing it not only as a path to financial independence, but to something more interesting to do with one’s day than clean the house and feed the children. And love, as sociologist Andrew Cherlin has documented, has undergone a transformation from married monogamy to something more open, flexible and often, of course, not heterosexual at all. Yet the way we talk about partnership — even the word “partner,” increasingly popular as a gender-neutral term, but also one oddly reminiscent of the workplace, the boardroom, the law firm — still reflects the origins of the family as a complementary institution to the job. When our relationships fall apart, we still blame ourselves rather than looking to all the social, institutional pressures that make it nearly impossible to continue them. Love is still just another form of alienated labor.

It’s not just romantic relationships that have suffered under neoliberalism. Friendship, too, is a casualty of the way our working lives are organized. A 2014 study found that one in 10 people in the United Kingdom did not have a close friend; in a 2019 poll in the United States, one in five of the millennials surveyed reported being friendless. The extended lockdown period of the coronavirus pandemic only exacerbated feelings of isolation that so many already had. People have tried to blame the internet for our collective loneliness, but in fact it comes alongside the change in our working lives and the decline of unions and other institutions that gave people a sense of shared purpose and direction beyond just the job. When I asked the union activists at the Rexnord manufacturing plant in Indianapolis what they’d miss when it closed down in 2017, they all mentioned their friends and the union. Not the work itself.

Work will never love us back. But other people will.

Concurrent political and ecological crises can seem overwhelming, but they have also done something else for us: They have created the possibility of imagining ourselves in a different world. If it was previously easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, we have now glimpsed both, and must now begin to think up something new.

As Alyssa Battistoni, a fellow at Harvard’s Center for the Environment, wrote, we cannot move forward “without tackling environmentalism’s old stumbling blocks: consumption and jobs”— and our culture of work itself contributes to the problem. Massive reductions in working time are not only desirable (as work is increasingly miserable); they are necessary.

Instead of turning our desires to the objects we can buy with the proceeds from our endless work, what if we turned our desires back onto one another? Spending time with other people has the potential to disrupt the entire economic system. The process of organizing, on the job and off it, is, after all, a process of connection. The first hesitant hello and the chat in the break room are ways of bridging the artificially created gaps between us to gesture toward the power we can have together. A union is only meaningful if the workers in it believe and act like a union, if they are willing to take risks to have one another’s backs.

To reclaim that space in which to find the connections that matter, we need something more than slight improvements in our individual workplaces or even massive overhauls of labor laws, though we need both of those things desperately. We need a politics of time. A political understanding that our lives are ours to do with what we will.

Society will always make demands of us, and a world that we built to value the relationships we have with others would perhaps make even more of them. But it would be a world where we shouldered those burdens equitably, distributed the work better, and had much more leisure time to spend as we like. It would be a world where taking care of one another was not a responsibility sloughed off on one part of the population or one gender, and it would be a world where we had plenty of time to take care of ourselves.

While we have to do our jobs for a living, it makes sense to make demands for better conditions. But alongside those demands, we should always be making demands to reclaim our time.

One of the things that the many social movements of the past decade or so have in common is a reclamation of public space in which to be with other people: the occupied squares of Spain and Greece; Occupy Wall Street; the protests of 2020, exuberantly reclaiming public space after months of lockdown to shout “Black lives matter!”

Those spaces were spaces of debate and of action, yes, but they were also spaces of care. The “food” and “comfort” committees at Occupy made sure not just that people’s basic needs were met but that they felt good in the space. There was singing and dancing, a library for borrowing books. “The media often deride the carnival spirit of such protests, as if it were a self-indulgent distraction from the serious political point,” Barbara Ehrenreich wrote in Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy. “But seasoned organizers know that gratification cannot be deferred until after ‘the revolution.’ ”

The teachers’ strikes that rippled across the United States after 2012 created anew the spaces of connection. The picket lines in Los Angeles and Chicago featured dance routines and new songs. The strike itself is a means of reclaiming time from work, a way to demonstrate the workers’ importance by halting business as usual, but also a way to stake claim to one’s time and creations. In the midst of the strike, utopia is briefly visible. And the mass strike, as Rosa Luxemburg wrote, has the potential to turn the world upside down.

These moments and spaces are insufficient, perhaps, to completely overhaul the system.

Imagining love alone as capable of change is idealism, it’s true. Freeing love from work, then, is key to the struggle to remake the world. And people are already reclaiming spaces to experiment with what it means to love one another without the demands of capitalist work patterns. Love, Silvia Federici argued, is a power that takes us beyond ourselves: “It’s the great anti-individuality, it’s the great communizer.”

Capitalism must control our affections, our sexuality, our bodies in order to keep us separated from one another. The greatest trick it has been able to pull is to convince us that work is our greatest love.

No comments:

Post a Comment