https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii126/articles/mike-davis-trench-warfare

This article was recommended by dmorista

We assume that times of great social upheaval and human peril produce equally dramatic political reactions: uprisings, counter-revolutions, new deals and civil wars. The one and only thing that most Americans agree about is that we are living in such a time, the greatest national crisis since 1932 or even 1860. Against a background of plague, impeachment, racist violence and unemployment, one party espouses a vision of autocratized government and a return to the happy days of a white Republic. The other offers a sentimental journey back to the multicultural centrism of the Obama years. (Biden’s promise of a ‘new new deal’ was for gullible progressives’ ears only.) Both parties are backward looking, solipsistic and unanchored in economic reality, but the first echoes the darkest side of modern history. The vote, held on a day when more than 100,000 Americans tested positive for covid-19, was supposed to deliver a definitive verdict on Donald Trump. Indeed the President’s increasingly frenetic attempts to delegitimize the election seemed to signal his apprehension of a Democratic landslide. In the event a projected 160 million ballots were mailed in or cast in person, representing the highest turnout rate in 120 years. A stunning judgement was expected.

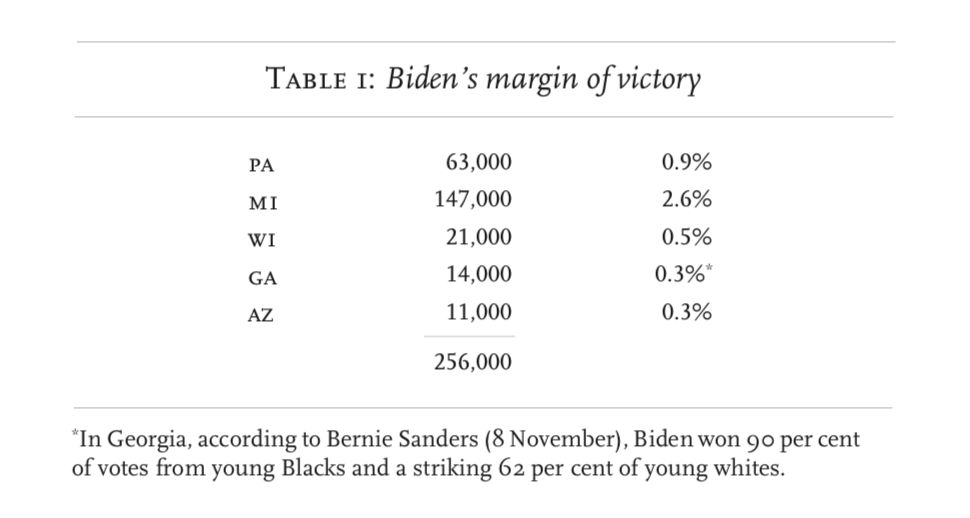

Instead the election results are a virtual photocopy of 2016: all the disasters of the last four years appear to have barely moved the needle. Biden eked out a slim victory, in some states only by microscopic margins, that won him 306 electoral votes, the same as Trump four years ago. A mere 256,000 votes in five key states purchased 73 of those votes. Meanwhile much of his popular vote majority of approximately six million, like Clinton’s previous 3 million, was simply wasted in blue trash bins like California, Massachusetts and New York without adding electoral votes.

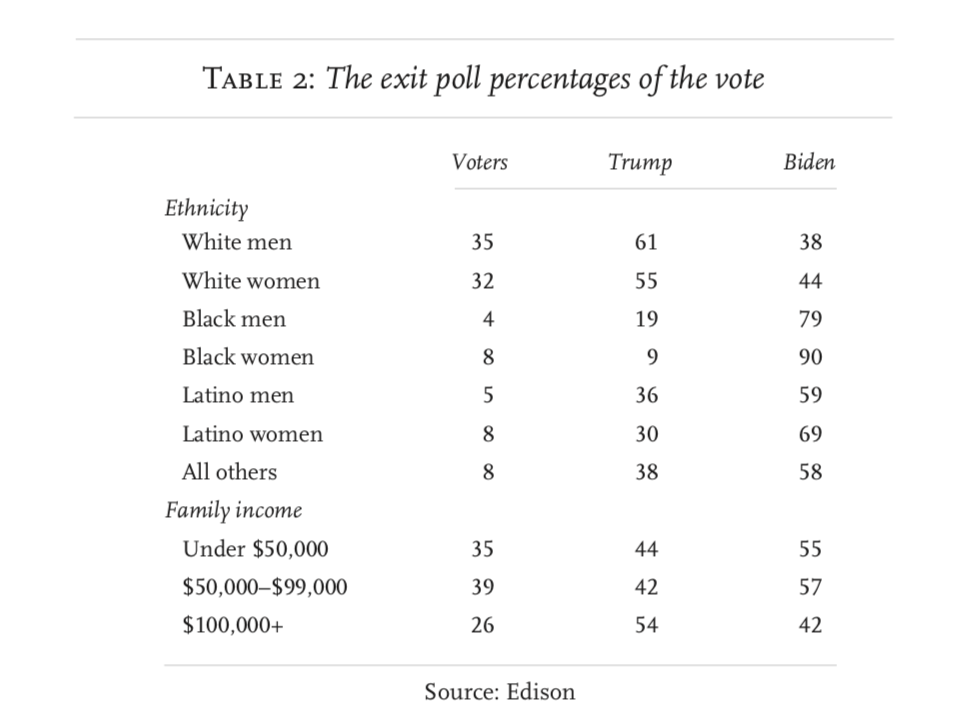

If Biden, as projected by Edison Research, has increased Clinton’s percentages amongst white men and possibly Catholics, Trump has improved his 2016 vote by similar margins amongst Black men, Asians and the upper middle class. Different exit polls give different estimates of the gender gap, but Edison showed only a one per cent increase (slightly more in the case of Black voters) compared to 2016. White women actually increased their preference for Trump while Latinas were more favourable to Biden than to Clinton—in both cases by 3 per cent. Although 60 per cent of ballots were still cast by people 45 or older, the under-30 vote was the one result that actually matched pre-election predictions: an increase in turnout from 42 per cent in 2016 to 53 per cent this year.1Otherwise ground was gained or lost by inches, not yards. However the results are spun, the House Divided remains standing with only some furniture moved around.

Despite an enormous campaign treasury, the Biden campaign only really struck fire where it converged with existing popular movements willing to take matters in hand: outstanding examples include Fair Fight, Stacey Abrams’s extraordinary voter coalition in Georgia, and Living United for Change in Arizona (lucha)—a Latino and labour united front built during the long struggle against the neo-fascist regime of Sheriff Joe Arpaio in Maricopa County (greater Phoenix). On the other hand, the Democratic infantry—the thousands of union members who traditionally go door-to-door for the Party—were on the whole stood down. Individual unions such as Nurses United, the American Federation of Teachers, the Las Vegas Culinary Workers and other locals of unite here undoubtedly made decisive contributions to Biden’s victory in certain states, but the national union profile was the lowest in modern history.

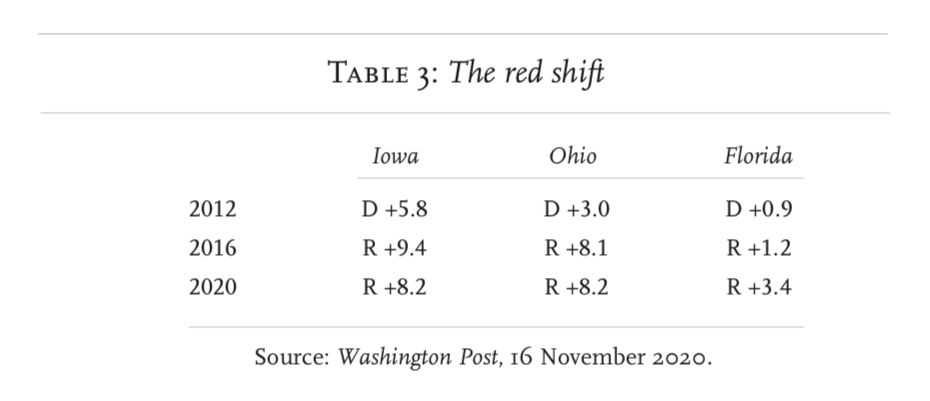

The Trump camp, in contrast, was willing to sacrifice some cadre to covid-19, and unleashed hordes of often unmasked mega-church faithful on the suburbs. While the liberal media was riveted on the unnerving spectacles of Trump’s virus-spewing mega-rallies, a huge grassroots campaign financed by his billionaire allies was rousing old supporters and adding new ones to its ranks. (The more important issue of non-Trump-core voters who rallied to his economic ‘recovery’ will be discussed later.) The effort increased his 2016 national vote by more than 8 million and preserved his 2016 winning margins in three key battleground states that Obama had won in 2012 and Biden had hoped to recapture. Democrats have to wonder whether these important ‘purple’ states have not now turned convincingly red.

Meanwhile the down ticket results were disastrous for those expecting a landslide. On the eve of the election the Democratic House Campaign Committee was boasting it would enlarge the party’s delegation by ‘five, 10 or even 20 seats’; instead they lost nine or more seats, leaving them with only a fragile majority. (The Democrats also failed to win a single one of the 27 races that the New York Times had labeled as ‘toss ups’.)2 ‘Moderate’ Democrats in the so-called Blue Dog Caucus, who had won seats in 2018, were the principal victims. The chair of the Campaign Committee, Cheri Bustos (d-il), admitted that she felt ‘gutted’ by the losses while Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez flailed the Committee for its incompetence in employing digital media.3

The billion-dollar Democratic crusade for control of the Senate also dismally failed expectations, producing only one victory and leading to the strange outcome that the body’s future will be decided by two run-off elections in Georgia in January, each a longshot for Democrats. (They haven’t won a runoff election in the state in 30 years.) If they do defy the odds and win control, Mitch McConnell, the most ruthless and successful Senate leader since lbj, can savour his extraordinary accomplishment of filling every single vacancy in the federal judiciary, from district courts to the Supreme Court, with bona fide members of the rightwing Federalist Society. He’s locked the federal court doors against Democrats for a generation and thrown away the key.

Since this is a census year, state legislative and judicial races have a special importance. Although California and five other states have delegated the job of redrawing state and congressional boundaries to independent commissions, legislatures still retain this power elsewhere. Over the last generation the Right has built an extraordinary infrastructure to support state-level political campaigns and promote the passage of legislation, particularly laws restricting labour, abortion and voting rights. It has three institutional components: 60 free-market policy institutes in all 50 states that are affiliated to the State Policy Network; the American Legislative Exchange Council (alec) which disseminates model right-wing legislation and helps Republicans write the bills; and Americans for Prosperity, the demiurge of the Tea Party movement, founded by the Koch brothers in 2004, which channels torrents of dark money into state races. In the 2010 midterm, following a carefully developed strategy called ‘Redmap’, the Republicans won 680 new legislative seats, the control of 54 chambers, and the resulting power to redraw district boundaries.

‘The rewards of gerrymandering’, according to the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, ‘are greatest in states with close partisan divisions, where over one-third of the seats can swing purely as a function of redistricting.’4 Accordingly Republicans in 2011 used state-of-the-art software to gerrymander key battleground states such as Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin. Republican statehouse majorities have proven all but unassailable. The Blue Wave merely lapped gently against this red fortress then rapidly receded, leaving behind the loss of the New Hampshire legislature to the Republicans. With the defeat of Democratic governors in Montana and New Hampshire, the Republicans now have ‘trifectas’ (control of both houses and the governor’s mansion) in 23 states. They also increased their majorities on state supreme courts, the final arbiters of the constitutionality of redistricting plans. New gerrymanders are now inevitable.5

If the Republicans retain the Senate as they are favoured to do, it’s hard to imagine a worse balance of power for the incoming Biden administration, its legislative agenda, and that of the progressive wing. Larry Cohen, the former president of the Communication Workers union who now chairs Our Revolution, the outreach arm of the Sanders movement, was uncompromisingly blunt: ‘For those of us who focus on governance and economic and social justices, this election is a dismal rubber stamp of the unacceptable status quo. Black, brown and white working Americans see their hopes of real reform evaporate for now, even while cheering the victory over Trump.’6

To understand how the Democrats arrived at such a hollow victory, it’s useful to begin with an examination of voting dynamics in strategic constituencies, comparing the outcomes to the 2012 and 2016 elections. County level totals can easily be retrieved from the New York Times election website, although serious demographic analysis of the vote, weighing gender, race, age, religion and so on, awaits the publication of the Pew Research Center’s invaluable reports. (Given the dismal performance of most polls, the interpretation of data based on voter sampling and exit polls, including those of Edison Research and the Associated Press’s VoteCast, should be viewed cautiously, to say the least.)

Down in the valley

For thirty years Texas with its 5 million conservative voters and 38 electoral votes has been the great powerhouse of far-right, post-Reagan Republicanism. Here, ‘dark money’ is literally pumped out of wells to fund right-wing operations and campaigns in every corner of the country. Especially when combined with Florida’s 29 electoral votes, Texas has been the counterweight to California’s liberal leviathan. But demographic change, where potentialized by activism, has been slowly eroding this hegemony. Anglos (non-hispanic whites) became a minority at the beginning of the millennium, and fully 40 per cent of the population in the 2010 census identified as Latino (Tejanos for the most part). One out of eight Texans are African-American and a huge influx of new immigrants, from farmworkers to software engineers, has added to the state’s kaleidoscopic diversity. Meanwhile Austin, whose youthful cultural energy exceeds that of any major city except New York, has become the most important tech centre between San Francisco and Boston, and last March delivered 84,000 primary votes for Bernie Sanders.

The Republican Party in Texas is highly mobilized, one might say even militarized, to prevent or postpone the transformation of this new demography into a Democratic majority. Its odd ally has been the Democratic National Committee, which for years has ignored Texas despite appeals from local Democrats that major investments in voter registration and community organization could shift the balance of power in the state and thus in the country. Their argument was fortified by Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 campaign against Ted Cruz which made up in grassroots energy much of what it lacked in cash. (Beto, following the Sanders example in 2016, rejected pac contributions.) Republicans laughed off the challenge in the beginning but sweated heavily in the homestretch when polls showed the candidates neck and neck. A large injection of cash from energy industry pacs ultimately saved the day for Cruz, but Democrats reveled in the closeness of the outcome, 50.9 to 48.3 per cent.

This year national Democratic money, much of it from Michael Bloomberg, arrived at the last minute to support a Beto-designed campaign that focused on ten heavily-gerrymandered Republican districts, mainly in the suburbs of metropolitan Dallas–Fort Worth, that he had won in 2018. Flipping nine of them would give Democrats control of the Texas House for the first time in nearly a generation. Misleading polls in October stoked optimism, even suggesting that Biden might win the state. In the event Republicans retained all the seats and Trump, although his margin was reduced, easily won. The Texas Observer, the state’s unique progressive magazine, concluded that ‘one of the biggest takeaways from the election is that there is a clear ceiling for Democrats in the growing suburbs . . . Now, Republican dominance of state government remains unfettered, as is the gop’s ability to lock in their majorities for years to come in the next redistricting cycle.’

The one-size-fits-all suburban template that was used by the Biden campaign in Texas and almost everywhere else ignored the consensus view of veteran campaign strategists from both parties that the real key to swinging the state is the mobilization of the ‘sleeping’ Latino majority in South Texas, especially in the seven major border counties where 90 per cent of the population is of Mexican origin. This was acknowledged two days before the election when Democratic National Committee Chair Tom Perez made a last-minute visit to the McAllen area. ‘The road to the White House’, he declared, ‘goes through South Texas. Remember, Beto lost by about 200,000 votes in 2018. We can make up these votes alone in the [Rio Grande] Valley. If we take Latino turnout from 40 per cent to 50 per cent, that’s enough to flip Texas.’ The strongly Democratic border is one of the poorest regions in the country, heavily dependent upon agriculture and nafta trade with Mexico, with a population routinely vilified by Republican propaganda as aliens and rapists. The Biden campaign seems to have believed that anti-Trump sentiment alone would add another 100,000 votes along the border without having to divert resources from the suburban battlefields. A blue wave along the Rio Grande from El Paso to Brownsville was taken for granted.

However when the fog of battle dissipated, Democrats were stunned to discover that a high turnout had instead propelled a Trump surge along the border. In the three Rio Grande Valley counties (the agricultural corridor from Brownsville to Rio Grande City) which Clinton had carried by 40 per cent, Biden harvested a margin of only 15 per cent. More than half of the population of Starr County, an ancient battlefield of the Texas farmworkers movement, lives in poverty yet Trump won 47 per cent of the vote, an incredible gain of 28 per cent since 2016. Further up river he actually flipped 82 per cent Latino Val Verde County (Del Rio) as well as Zapata County, which no Republican has won since the end of Reconstruction. In addition he increased his vote in Maverick County (Eagle Pass) by 24 per cent and Webb County (Laredo) by 15 per cent. Rep. Vincente Gonzalez (D-McAllen) had to fight down to the wire to save the seat he won by 21 per cent in 2018. Even in El Paso, a hotbed of Democratic activism, Trump made a 6 per cent gain. Considering South Texas as a whole, Democrats had great hopes of winning the 21st congressional district which connects San Antonio and Austin, as well as the 78 per cent Latino 23rd, which is anchored in the western suburbs of San Antonio but encompasses a vast swathe of southwestern Texas. In both cases, Republicans easily won.

The explanation for the Trump surge? As Congressman Filemon Vela (D-Brownsville) bitterly complained to a Harlingen newspaper, ‘I think there was no Democratic national organizational effort in South Texas and the results showed. The visits are nice, but without a planned media and grassroots strategy, you just can’t sway voters. When you take voters for granted like national Democrats have done in South Texas for 40 years, there are consequences to pay.’ But the Border was equally neglected by Clinton in 2016, so additional variables must be involved. Some suggest that right-to-life Catholicism and the appointment of Coney Barrett generated extra enthusiasm for Trump while others point to the fact that ice is a major employer in these counties (indeed, sometimes the only high-wage employer). Fear of a refugee wave swamping border counties might also have been a factor, along with Obrador’s strange bromance with Trump. The Republicans energetically mined such inclinations, but I doubt this was decisive. More important were other trends, rooted in the region’s political economy and class dynamics, that favoured both the right and the left.

First, nafta as well as the shale oil boom in the Laredo area has greatly expanded the entrepreneurial class in the border counties—independent truckers, shipping agents, warehouse foremen, oil and gas sub-contractors, car dealers, and the like—whose natural magnetic orientation is Republican. Since the border economy is capitalized on poverty and low wages, this group has a keen interest in opposing a higher minimum wage or a pro-union Labor Department. Republicans have avidly responded to new opportunities to recruit leadership from this dynamic stratum. In his 2014 campaign Republican Governor Greg Abbott made no less than 20 trips to the Valley.7 Although Trump initially jeopardized their livelihoods with his threat to withdraw from nafta, the 2018 treaty revisions with Mexico left the status quo largely in place and freed the tejano business community to vote its wallet. (Nationally, the Latino share of the ‘middle class’, as the Brookings Institution defines it, has grown from 5 per cent in 1979 to 18 per cent last year. In contrast the Black share has only increased by 3 per cent in 40 years, from 9 per cent to 12 per cent.)8

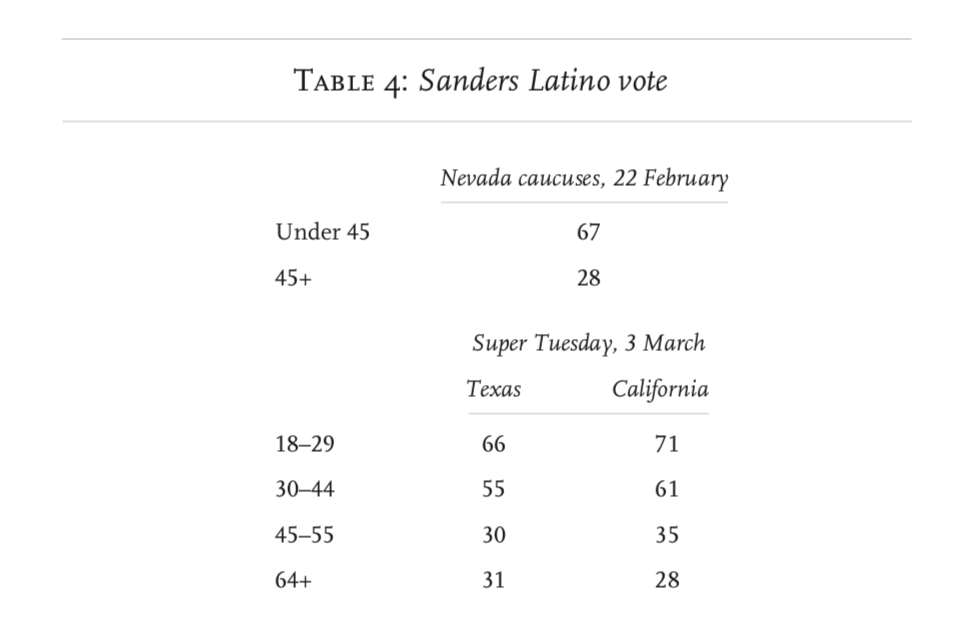

On the other side of the ledger, there was a spectacular wave of support in South Texas for Bernie Sanders during the March ‘Super-Tuesday’ primary. After the withdrawal of San Antonio’s favourite son Julián Castro from the race at the beginning of January (he immediately endorsed Elizabeth Warren), rank-and-file tejano Democrats rallied to Sanders. With 200 young Latino organizers working full-time for his national campaign and helping shape its strategy, Sanders was able to speak to the Valley communities with a passionately informed voice. As was the case with the Nevada caucuses in February, radicalized Latino youth and their working-class families embraced his platform of universal healthcare, free public higher education, a $15 minimum wage, and pathways to citizenship for undocumented populations. Sanders swept the entire border from Brownsville to El Paso as well as San Antonio and metro Austin, winning 626,000 votes, 99 convention delegates and 30 per cent of the votes cast, just 5 points behind Biden. (If the Warren vote is combined with Sanders, the left wing of the party outpolled Biden by 140,000 votes.)

The Sanders campaign was also an uprising against a conservative Democratic machine led by old pols like Rep. Henry Cuellar of Laredo, a former customs broker who belongs to the Blue Dog caucus and frequently votes with Republicans. Jessica Cisneros, a 26-year-old human rights attorney backed by Sanders and the progressive organization Justice Democrats, came very close to beating him in March. Biden’s nomination and Cuellar’s narrow victory were twin disappointments that deflated the enthusiasm of Sanders’ voters, ratifying the widespread perception that centrist Democrats give no priority to fighting for the interests of the Border working class.9

Spanish-surname people are the biggest minority in the United States and this year surpassed African-Americans as the second largest pool of eligible voters. Their electoral clout will only increase: amongst the first wave of GenZ eligible voters (age 18–23) Latinos constituted 22 per cent, Blacks 14 per cent.10 In the Bush years many Republican strategists in the Sunbelt, having read the demographic tea leaves, argued that culturally conservative Latinos were the key to building a new and more durable Republican majority. Mainstream Democratic leadership, however, has never endorsed a similar vision and continues to treat Latinos as second-class citizens within the party hierarchy who will automatically vote for Democratic candidates. The exclusion of Julián Castro from the speakers’ platform at the virtual convention in August was interpreted in the Spanish-language media as salt rubbed in an old wound. The Democrats have other neglected or abandoned constituencies, including Puerto Rico and Appalachia, but South Texas has a unique strategic importance.11

Leaving the rust on the rustbelt

The famous 77,000 votes from Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania that put Trump in the White House in 2016 can be situationally explained in any number of ways, including Comey’s bombshell announcement about Clinton’s email files, lower than expected Black turnout, a shift of Catholic pro-life votes to Trump, Clinton’s absorption with suburban voters and her failure to campaign in older industrial towns, and so on. But it’s indisputable that Trump succeeded in winning over significant numbers of former Obama voters, many of them union members, in rustbelt counties that were organized by the cio in the 1930s and were for generations rock solid Democratic. This was alarming since it seemed to correspond to the electoral success that far-right populist parties in Europe have enjoyed in similarly depressed economies such as the north of England, the French Nord, and eastern Germany. And because so many of these Trump voters had been supporters of the first Black president, it was not obvious that they were motivated by the same kind of racism that infused the northern Wallace vote in 1968 and produced so many Reagan Democrats in 1980.

The 2016 election returns, I argued at the time, held less mystery than many believed. Rather than a historic realignment of social forces, Trump won nationally because he was enabled by his gift of the Republican platform to the Christian right to preserve (but not increase) the 2012 Romney vote, while Clinton dramatically underperformed Obama in the Great Lakes and Midwest. Nevertheless what did happen that year in old smokestack towns like Erie (pa), Warren (oh) and Dubuque (ia)? I selected for study 15 industrial counties that had voted for Obama (with two exceptions) in 2012 and then switched to Trump. Using local media, I correlated the Democratic defeat to recent plant closures and job losses that presumably generated high levels of economic anxiety that Trump addressed more directly than Clinton.12 At the time I had little information about the sex, age, race, income, etc. of voters, so I was only able to measure one dimension of the ‘Obama Republican’ phenomenon which is usually characterized as white males with only a high school education. The ground truth was undoubtedly more complex.

Revisiting these counties today reveals only marginal change in relative electoral positions. In 2016, Trump flipped 8 of these traditionally Democratic counties, although in all cases the 2012 Democratic margin was substantially cut (from 8 per cent in Moline, Illinois to 29 per cent in Warren, Ohio). Biden won back Erie (pa) and Saginaw (mi) counties, but lost Mahoning, Ohio (Youngstown). Only in Rock Island County, Illinois (Moline) did he fully repair the 2016 damage. In three previously Trump-won counties, Biden was unable to match the Clinton vote, and where he did improve on her totals (9 counties) it was only by an average of 3.4 per cent, leaving most of Trump’s 2016 gains in place. As for cases where Trump increased his margins by 1 per cent or more (7 counties), these results can be entirely explained by simply adding the 2016 Libertarian vote to his vote that year. But overall there was no surge, blue or red, and much of the rustbelt vote looks like it did in 2016. Higher turnouts seem to have inflated totals with only minor changes in composition.

The continuing Democratic deficit relative to 2012, however, remains more a Trump vote than a Republican vote. Election returns in these counties and their core cities reveal much higher levels of support for local Democratic candidates and their pro-union positions than for Biden. In light of Clinton’s debacle he was more attentive to such places, but no better prepared to answer the question that every rank-and-file Democrat or former Democrat in the older industrial states has been asking for more than a generation: ‘What will you do to increase job opportunities and economic security here in Erie (or Laredo or Camden or Wilkes–Barre and so on)?’ ‘Millions of green energy jobs’—Biden’s mantra—is an abstraction that utterly fails to connect to the concrete circumstances of people like the locomotive builders laid off after their 2019 strike against ge in Erie or to the J. C. Penney salespeople in Brooklyn thrown out into the street in late September after Amazon drove the famed department chain into bankruptcy. A whole generation of first-in-the-family college graduates—now working as peons for Uber or delivering groceries for Amazon—are unlikely to imagine their future as solar panel installers or software technicians for an otherwise fully automated trucking company. For every ‘green power’ job created, automation and depressed demand will probably dispose of five or ten traditional jobs.

Real solutions demand geographically targeted public investment, control over capital flight and financial outflows, regional economic planning, and, above all, a massive expansion of public employment and public ownership. This is a road that few elected Democrats apart from the open socialists in the ‘Squad’ are prepared to go down or even consider, no matter how much it corresponds to needs at the grassroots. In fairness to mainstream American liberals, however, neither the British Labour Party nor the big continental social-democratic parties have found the will to forcefully address similar questions of regional economic decline and high, structurally consolidated levels of youth un- and under-employment.

The land of lumpen billionaires

The great Republican upset was not Trump’s slim victory in 2016 but, following this, his rapid take-over and ruthless cleansing of the gop in 2017–18. No one, as far as I know, predicted this, especially in the face of the impressive range of his intra-party opponents which included the Bush dynasty, old Reaganites like John McCain and Mitt Romney, and even for a season the party’s own Jacobin Club, the Freedom Caucus. Many were appalled by his willingness to unleash the alt-right against the campaign of any Republican who hesitated to pledge unconditional obedience to the White House, and dozens eventually chose early retirement. Trump’s nuclear advantage was his astounding popularity at the base, a frenzy routinely stoked by evangelical leaders, Fox News and, of course, his endless tweets. Suddenly the America depicted by the Occupy Movement as the People versus the greed of the One Percent, was unmasked as something entirely different, a confused majority facing the militant and intransigent Forty Percent. It’s the Trump Base—worshipful, fanatic and impervious to reason—that has made Trump so scary to the majority. If they live in big cities and depend on cnn and the New York Times to access reality in the red states, Trump rallies most likely define their image of the other America: big, angry and ignorant white people in maga hats baying at the moon or beating up journalists. In the liberal press they read that Trumpdom is rural and small-town America self-transformed into a Third Reich, with a declining white proletariat in tow.

This recalls the ‘Bubba’ phenomenon in the civil rights era where Southern defenders of Jim Crow were depicted as tobacco-chewing good ol’ boys who worked at gas stations or lounged menacingly in front of country stores. As Diane McWhorter demonstrated in her brilliant history of the Birmingham freedom movement, the Bubbas as well as Bull Connor’s brutal cops were just the hired hands of the country club elite, including her wealthy Klan-supporting father. The true enemy of racial justice was the city’s white bourgeoisie.13 Similarly, to understand contemporary far-right Republicanism, it’s necessary to look behind its populist facade to see how power is actually configured. Two social landscapes are particularly important for such an investigation: first, the ‘Micropolises’, smaller non-union, culturally conservative cities of the Midwest and South; and second, ‘Exurbia’, the affluent white migration into rural counties at the edge of major metropolises. The country hicks wearing John Deere caps who swoon for Trump on camera are only bit actors in the drama.

If Reagan came to power aligned with a historic anti-union offensive led by the Business Roundtable—a coalition of Fortune 500 corporations—Trump came to the White House thanks to the love of Jesus and a motley crew of what Sam Farber refers to as ‘lumpen capitalists.’ Although defence contractors, the energy industry and Big Pharma pay their dues to the White House as is always the case when Republicans are in power, the donor coalition that financed the revolt against Obama and after the defeat of Cruz in the primaries, united behind Trump, is largely peripheral to the traditional sites of economic power. In addition to family dynasties, mainly based on oil wealth like the Kochs, who have been around since the days of Goldwater and the John Birch Society, Trump’s key allies are post-industrial robber barons from hinterland places like Grand Rapids, Wichita, Little Rock and Tulsa, whose fortunes derive from real estate, private equity, casinos, and services ranging from private armies to chain usury. A vivid example of their world is Cleveland—not the faded grande dame on the Cuyahoga, but the seat of Bradley County, Tennessee.

A low-to-medium-income city of 43,000 east of Chattanooga, it is what the census now dubs a ‘micropolitan statistical area’.14 Over 90 per cent white and emphatically evangelical with 200 Protestant but only one Catholic church, Cleveland fits the Red America stereotype with almost cartoonish perfection. Thanks to Tennessee’s emergence as the hub of the southeastern auto corridor, and particularly to the big Volkswagen plant in nearby Chattanooga, it has attracted a surprising number of new factories, especially auto parts manufacturers, all of them basking under Tennessee’s low tax rates and right-to-work law. This year Trump won 77 per cent of the vote, exactly the same as in 2016. Unusual for a town its size, Cleveland has two billionaires in residence, both Trump beneficiaries as well as contributors.

One is Forrest L. Preston, net worth $1.8 billion, who owns Life Care Centers of America, the largest nursing home chain in the county with 220 facilities in 28 states and 30,000 employees. The long-term-care industry collects most of its income from Medicaid and Medicare, and Life Care was accused by a whistle-blower of routinely filing false claims, keeping patients in facilities longer than needed and charging for unnecessary procedures. Faced with the possibility of prosecution, Preston agreed in 2017 to pay back $146 million dollars to the Justice Department. The whistle-blower additionally alleged Preston was purposely bleeding the company dry and leaving it severely undercapitalized. Together with the other major chains, mostly owned by private equity companies, Life Care cuts costs by violating state and federal regulations about protective equipment, infection training and sanitation standards.15 The Trump administration punctually responded to industry lobbying by eliminating an Obama requirement for nursing homes to have at least a part-time infection technician and drastically reduced fines for noncompliance; in effect, subsidizing continued criminal negligence.16

The first major us covid-19 outbreak occurred in Life Care’s facility in Kirkland, Washington. The management waited two weeks before notifying public health officials of its cluster of pneumonia cases, and after coronavirus was identified, concealed the number of infections and casualties, refused to give any information to frantic families, and forced staff to work for weeks without proper protection. By the beginning of summer 45 patients, workers and people in contact with staff had died from covid-19. Numerous other Life Care homes, unable or unwilling to practice effective infection control, also registered frightening death counts: 17 dead at the Nashoba Valley centre outside Boston; 8 dead in Omaha; 5 in Hilo, Hawaii; in Tennessee, at least 14 dead in McMinn County and 17 dead in Hamblen County facilities; and so on.17 (On its website the company offered the consoling message ‘Dealing with Death and the Joy that Awaits’. More recently, it built a small memorial to heroic employees at its Cleveland headquarters.)

cbs’s 60 Minutes, pbs’s Frontline, the Washington Post and the New York Times all produced exposés about Life Care Centers, but the Trump administration and Republican state governments have aggressively shielded it and the rest of the industry from prosecution. During the first six months of the crisis, federal inspectors from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services routinely absolved facilities for flagrant violations of infection control regulations, and at least 18 Republican states have granted them at least limited immunity from lawsuits related to pandemic deaths. McConnell and the Senate majority meanwhile have made blanket immunity for nursing homes and hospitals a condition for progress on stimulus bills.18 Instead of fines or indictments, Life Care Centers received $48 million in pandemic relief funds.19 By election eve more than 100,000 had died in nursing homes nationwide and infections were again spiraling out of control, with staff continuing to work without adequate protective gear. Life Care’s share of the carnage is unknown since it refuses to release figures, but the reputational damage has been severe. As his profit centres turn into mortuaries, Preston has doubled down on his longtime avoidance of the press and unwonted publicity.

Not so for his neighbour and Cleveland’s other billionaire, Allan Jones, whose extravagant lifestyle and personality overflows Cleveland in all seasons. Jones owns Check Into Cash, the second largest payday loan company in the country, with 1,200 locations in 32 states, and he’s widely considered as the ‘father of payday credit.’ If you have lost your wallet or purse with all your cash, Jones will lend you $200 if you agree to pay back $230 next payday. If you can’t pay all of that on time, he’ll happily lend you more on the same terms. Soon you wake up in a world of pain. Usury is supposed to be illegal and most states have put a maximum cap on interest. But Jones pays politicians to bend the law for him. Not bribes under the table, but full-press campaigns by armies of overweight lobbyists. His home state has been particularly kind to him, and usury redefined allows him to live, next to Preston, in an oversized French chateau, modeled after the famous Vanderbilt estate, with a second home and horse ranch outside of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In an interview with the Huffington Post, he was asked why Cleveland had such a small Black population, less than half of the statewide average. He replied: ‘We have just enough blacks to put together a decent basketball team—but not so many the good people of Cleveland, Tennessee need to worry about crime. That’s why I can leave my keys in the car with the door unlocked.’20 In 2017 he became a hero to President Trump and Fox News when he yanked his companies’ ads off nfl primetime. ‘When I see Colin Kaepernick lecturing the “oppressed” wearing a Fidel Castro T-shirt you realize the hypocrisy to this stupidity. I love America. Our companies will not condone unpatriotic behavior!’21

Exurban strongholds

Preston and Jones belong to a world that still retains some resemblance to that described in Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt, a 1922 novel that chronicled a Main Street culture of business corruption, coercive conformism, fundamentalist fervour and virulent nativism. Exurbia, on the other hand, is the brave new world created by the flight of affluent white Republicans to rural areas rich in scenic and recreational amenities. In spite of being obsolete for decades, the old triad of city–suburb–country still structures and distorts the interpretation of elections. The unitary category of the ‘suburban vote’ is especially misleading since it conflates the very different social universes of older, poorer and more diverse inner-ring suburbs with newer and wealthier outer-ring suburbs and edge cities. The former became more Democratic in the Clinton era while the latter have begun to shift since Obama, powered by a growing in-migration of middle-class minorities and liberal whites. But suburbs are no longer the big story, at least from the standpoint of geographers and political sociologists. ‘Despite the common perception that the us has become a “suburban nation”’, write Laura Taylor and Patrick Hurley, ‘exurbia has emerged as the dominant settlement pattern across the country, characterized by different patterns of development and lifestyle expectations from cities, towns, and suburbs, with houses in scenic, natural areas on relatively large acreages.’22

Rural gentrification by in-migrants from large metropolitan areas has created something resembling Blade Runner’s Off World. In an important Brookings Institution study published in 2006, exurbs were defined on the basis of housing tracts having a maximum housing density of 2.6 acres per unit that had grown by at least 10 per cent during the 1990s with a minimum of 20 per cent of the working population commuting to jobs in an urban place. Most were located on the outer edge of metropolitan areas, but a significant minority were outside the borders in counties still designated as rural. Based on the 2000 census, Brookings estimated a national exurban population of 10 million, 70 per cent of whom lived in the South and Midwest.23 Since then exurbs, enabled by platform capitalism and virtual commuting, have more than tripled in population to 34 million, and Bain & Company’s Macro Trends Group projects that they will surpass the urban centre population within the next generation.24 This exodus consolidates the new patterns of racial and political segregation that the journalist Bill Bishop famously characterized in 2008 as ‘The Big Sort’.25

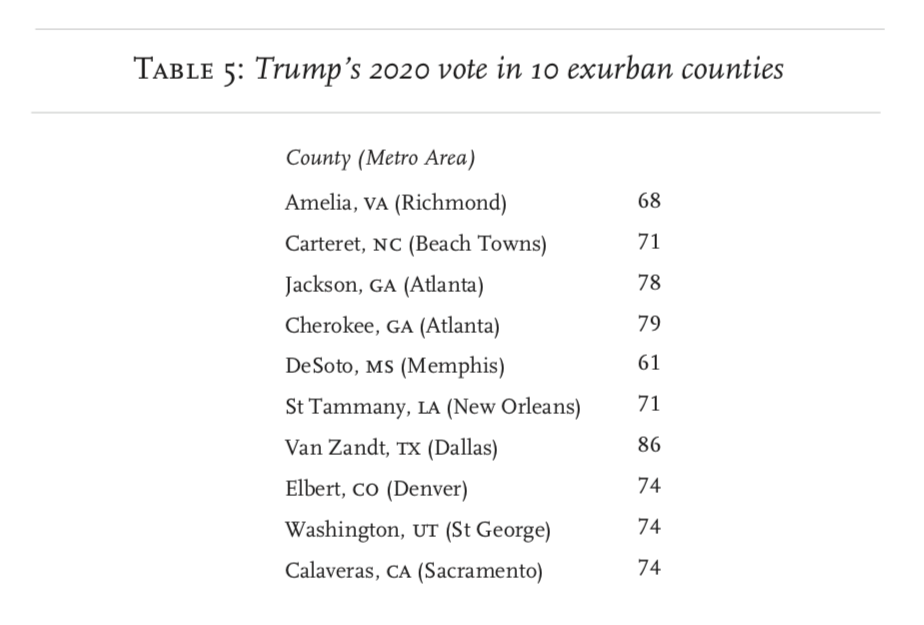

In the middle and south of the United States especially, the exurban ‘sort’ has countered population decline in small Republican cities and farm counties. Despite syndicated columnist and sprawl aficionado David Brooks’s startling 2017 prediction that the exurbs would someday become the new ‘Democratic heartland’, the opposite seems to be the case. Although there are some solidly blue exurbs—for instance, Buncombe County (Asheville), nc and Mendocino County, ca—they remain exceptional. Trump won the exurban vote (222 counties) by a whopping 17 per cent in 2016, a majority that Biden is unlikely to have eroded.26 Once again the exurbs roared.

False choices

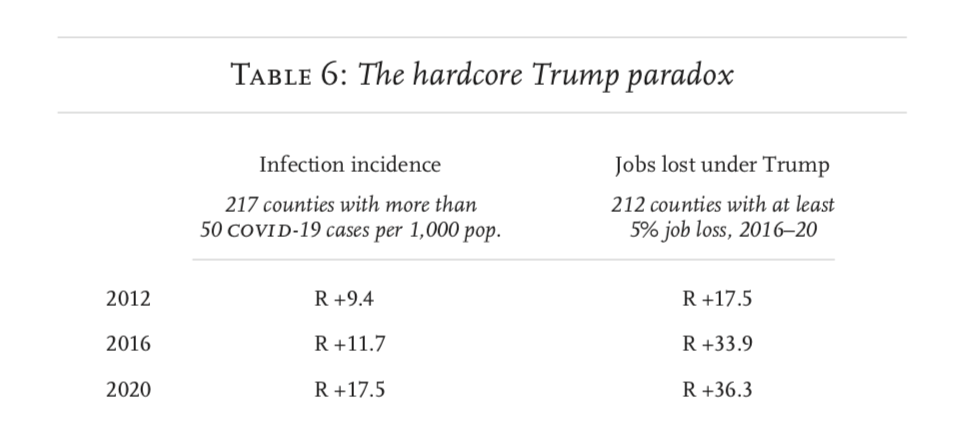

Trump is the first modern American president never to enjoy a majority approval rating in national polls. On the other hand, he’s had unwavering support from a consistent 40 per cent of the eligible voting population.27 Their love for Trump has not been diminished by scandal, broken promises, a quarter-million covid deaths, or eight million people suddenly cast into poverty. Because so many of them live in informational environments dominated by Fox News and the 800 radio stations owned by far-right iHeartMedia (formerly Clear Channel Communications), which broadcasts Rush Limbaugh, Trump’s fictions are rarely fact-checked or contested. Polled on election eve, for instance, only a quarter of declared Republican voters considered either the pandemic or climate change a major concern. Despite October’s dramatic spike in covid-19 cases in the upper Midwest and South, Trump actually increased his vote in affected counties, just as he did in areas of substantial job loss since 2016.28

Assuming, albeit unscientifically, that the 40 per cent ratio can be applied to the total vote, that’s 55 million voters. Since he has 80 million followers on Twitter, many too young to vote or disinclined to participate, 55 million may be a decent approximation of the hardcore component of his 73 million votes.29 But who are the other 18 million Trump voters, the ‘softcore’ who annulled a Democratic landslide? A Pew survey of registered voters conducted in the second week of October revealed that the top issue was the economy (35 per cent), followed by racial inequality (20 per cent), the pandemic (17 per cent), crime and safety (11 per cent) and the Affordable Care Act (11 per cent). (As for climate change, an earlier Pew sampling found that two-thirds of Biden supporters considered it ‘very important’ in influencing their vote, but only one in ten Trump voters agreed.) Without downrating the influence of the Trump camp’s incessant and factually absurd depiction of Black Lives Matter protests as violent riots led by communists, it seems reasonable to assume that jobs and income were the major factor in the ‘soft Trump’ vote.

This is the analysis, at least, of most of the commentariat. It became obvious in the spring after Trump encouraged armed demonstrators to storm state houses, demanding the ‘liberation of the economy’ from quarantines imposed by Democratic governors, that his campaign would do everything possible to counterpose jobs and income to public health measures. The corresponding Democratic priority was to prevent such a division of issues, presenting Biden as the authentic jobs candidate who would revive the economy through an aggressive national plan to contain the pandemic and ensure safe working conditions by a full use of federal power to produce ppe and ratchet up workplace inspections. He was given multiple opportunities to take the offensive and win the jobs vote. The first was in April and May when tens of thousands of healthcare and Amazon workers went into the streets to protest dangerous working conditions. Both Sanders and Warren cheered the strikes and offered supportive legislation, but Biden remained silent in his basement in Delaware. After maskless Memorial Day celebrations egged on by Trump stoked infections to record levels, he had an opportunity to steal the Republicans’ pants and launch an ad campaign about the White House’s threat to the recovery. He didn’t.

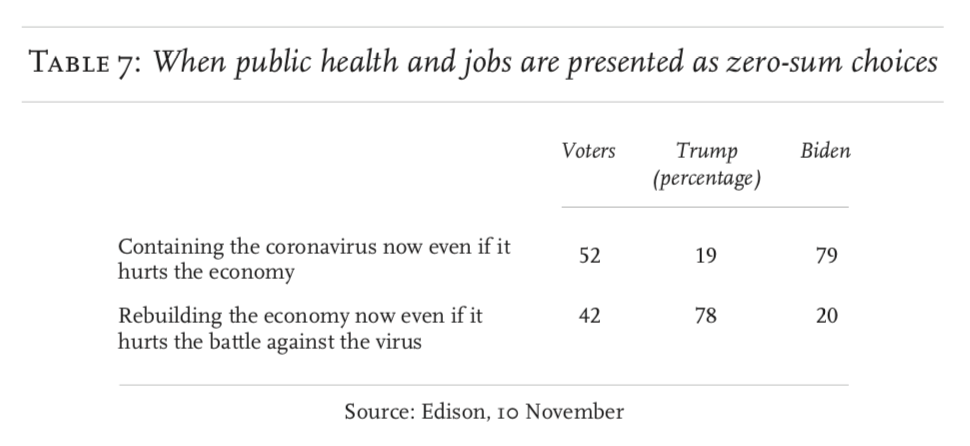

Most importantly, the debates on the stimulus bills should have unleashed grassroots actions by unions and community organizations in support of the Democratic proposals. Instead Pelosi locked progressives out of the discussion and conducted private negotiations with Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin. By October millions of people were desperately waiting for a new relief package to pay rents, mortgages and doctors’ bills, but Pelosi refused to accept the $2 trillion package offered at the last minute by the White House. As Hadas Thier, writing in Jacobin, repeatedly pointed out, the Trump offer may have been a grandstand stunt, but if Pelosi had embraced the compromise it would have riveted public attention on the refusal of McConnell and his Senate minions to consider relief spending on the same scale as earlier bills. This would have given both Biden and Democratic Senate candidates powerful ammunition to use in the final exchange of fire. Instead Pelosi and the leadership ‘took a gamble and assumed that failed negotiations would further hobble the Republicans at the polls and doom Trump’s reelection prospects, even if it meant risking no deal at all. This left millions in the lurch, exposed their own cynicism, and ultimately allowed Trump to feign more interest in providing economic relief than the Democrats.’30 Millions of worried voters as a result were presented with a zero-sum choice that should never have been necessary.

Justice Democrats, a political action committee founded by veterans of the Sanders Campaign and supported by Nurses United, offered a scathing judgement on Democrats’ failure to project convincing economic alternatives in their congressional campaigns. ‘In an election where the economy was voters’ top concern, many Congressional Democrats had no discernible economic message . . . After the Democratic convention the party’s lack of an economic message was clear. As Ron Bronstein, senior political analyst for cnn, observed, the convention “had a conspicuous blind spot: The event did not deliver a concise critique of Trump’s economic record” despite an abundance of opportunities to do so. In poll after poll, Trump led Biden on the economy.’ Although Biden eventually reclaimed some ground amongst young voters and swing voters with his green jobs proposal and ‘was buoyed by voters’ faith in his ability to handle the pandemic, that support did not extend to Congressional Democrats. They failed to fill the void with anything resembling a coherent economic message. Predictably on election day exit polls showed that the economy was voters’ top issue. And predictably, down ballot Democrats paid the price for their lack of an economic message.’31

Economic debacle

Trump, of course, was aided by the image of a strong recovery that the third quarter job report painted, as well as soaring home sales fuelled by low interest rates and the addition of 638,000 new jobs in the weeks before the election. But the fall’s recovery is already proving to be a mirage. Half of October’s job gain was in retail, bars and restaurants and is now fast evaporating as the dread second wave forces new shutdowns on reluctant states and cities. Without new loans and increased consumer demand, tens of thousands more small businesses will close or be devoured by Amazon in an almost Weimarian auto-da-fé of the petty bourgeoisie. (According to the industry, more than 100,000 restaurants have already permanently closed their doors.)32 Trump, of course, is happy to leave behind as much chaos and economic wreckage as possible to greet the new inhabitant of the White House. On New Year’s Day, the moratorium on student-debt repayments will end, supplemental weekly payments to the unemployed will expire, and no more stimulus cheques will be issued. To forestall this disaster, the Democrats in the lame-duck House may reopen negotiations with the Senate. But there is little chance that McConnell will agree to anything other than the miniature stimulus package, heavily skewed to the Republican donor class, that has been his sticking point since the end of the summer. (As Olugbenga Ajilore, a senior economist at the Center for American Progress, commented: ‘To say we don’t need as much aid is ridiculous. What that signals is that all we care about is white men and no one else.’)33

If the deadlock continues until the Inauguration, Biden will face a perfect storm of soaring coronavirus deaths and renewed economic desperation. On the pandemic front, he’ll be appropriately girded for battle with a federal pandemic strategy, designed and led by scientists, and an increasing supply of new vaccines. But its implementation must first clear the hurdle of underfunded state preparations to distribute the vaccine, especially to the most vulnerable populations. Trump in his war against blue states and cities has allowed only a trickle of aid to reach their public health departments—a contrast to the billions that he has fed to Big Pharma. The Democrats will need to rectify that as soon as the moving vans arrive at the White House, otherwise the vaccine rollout will become a chaotic mess.

But it’s the lack of a coherent economic strategy, one that speaks especially to the working-class people who ticked that box for Trump, that could turn Biden’s first one hundred days into a fiasco. Democrats must quickly pass a stimulus package large enough to sustain purchasing power, save cities and states from bankruptcy, and prevent a collapse of investment in the real economy. The ‘Heroes Bill’ passed by the House on 1 October, and then sequestered in the Senate, authorized a relief budget of $2.2 trillion; by the end of January, however, the economy could be headed south so fast that double that amount might be necessary to turn on the Keynesian ignition. But if McConnell retains control of a Senate majority, he’ll again have the power to veto or downsize whatever the Democrats propose. In order for Republicans to sweep the House two years from now, he’ll try to keep economic and social turmoil at a simmer if not a boil.

Biden’s acceptance speech, particularly his passionate promises to heal divisions and work collegially with his old friend Mitch, were symptoms, to put it mildly, of a strange variety of Stockholm Syndrome. Since Newt Gingrich declared war to the bone against Bill Clinton in 1995, the only thing that most Republicans are willing to reciprocate to conciliatory gestures are more bullets. Until they can dethrone the Majority Leader, the Democrats have little hope of passing the ‘public option’ amendment to the Affordable Care Act, lowering the age for Medicare to 60, or creating the pathways to citizenship that Biden promised to immigrants during the campaign. The proposed constitutional reforms that generated such enthusiasm during the Democratic primaries—the elimination of the electoral college, the restoration of the campaign finance reform laws struck down by the Supreme Court in 2010, statehood for dc and perhaps Puerto Rico—are dead on arrival and will likely gather dust for another decade.

Civil war served cold?

This grim scenario is not, as some defeated Blue Dogs instantly claimed, the fault of Black Lives Matter and the Progressive Caucus. On the contrary, progressives did well in the election, retaining all their Congressional seats and adding new stars to the Squad’s firmament: Jamaal Bowman in New York, Marie Newman in Chicago and Cori Bush in St Louis. All the incumbents in swing districts who had co-signed Medicare for All were reelected, and more than a dozen progressive state ballot measures—including a $15 minimum wage in Florida—were passed even in the face of Trump majorities. (The great exception, paradoxically, was California where a flood of corporate money defeated important initiatives backed by unions and renters.) The Progressive Caucus, moreover, has launched an aggressive campaign to ensure that Biden allots some key cabinet posts to the left; high on the list are Sanders as Labor Secretary and Warren as Secretary of the Treasury or Education. This is the acid test that will determine progressive attitudes toward the new White House.

The activist base, moreover, is only tenuously tethered to a strategy built on the premise that the Democratic Party can eventually be won to the left. Sanders’s defeat in the primaries was deeply demoralizing to his supporters and was made even worse by his unexpected concession to Biden negotiators of the movement’s signature issue: a universal single-payer healthcare system.34 Black Lives Matter fortuitously rescued dispirited Sanders activists, keeping them on the streets and channeling many into local get-out-the-vote campaigns. But blm has reached its own crossroads, with ‘defunding the police’—perhaps a poor slogan but an entirely necessary demand—now anathema to even the most progressive Democrats. With the hopes of low-wage workers crushed by economic disaster, activists broadly agree that a more explicitly class-based and ethnically inclusive organizing strategy is needed, while simultaneously preserving the demands and experience of blm as well as the leadership role of young women of colour. But there is no immediately obvious organizational nucleus around which a new mass politics, bridging social democratic reform and extreme economic conditions, can cohere. What was most electrifying during the primaries and more locally during the final campaign was the grassroots initiative and fighting spirit displayed by young people of colour, Generations X and Z. The progressive electoral project by itself is too mortgaged to short-lived hopes to sustain such activism, especially in the shadow of a congressional stalemate, which is why the goal must be the creation of more ‘organizations of organizers’ offering niches that allow poor young people, not just ex-graduate students, to lead lives of struggle.

Finally what is the big picture of this election? For a cool observer like Brookings’s William Galston, predictions of a Democratic landslide were inherently improbable given the monolithic nature of voting blocs in recent elections and the disappearance of split voting. ‘We live in an era of closely contested presidential elections without precedent in the past century . . . Contrast this picture with the results of the presidential elections between 1920 and 1984 . . . In that 64-year period, the contest between the two parties resembles World War Two, with a high level of mobility and rapid gains and losses of large swaths of territory. By contrast, the contemporary era resembles World War One, with a single, mostly immobile line of battle and endless trench warfare.’35 Writing in Foreign Affairs, Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue put this in an international context: ‘A powerful alignment of ideology, race and religion renders America’s divisions unusually encompassing and profound. It is hard to find another example of polarization in the world that fuses all three major types of identity divisions in a similar way.’36 Gridlock, according to all three, has simply become the default condition of American politics. Republicans are vexed because their share of the popular vote is ‘stuck in a narrow range between 46 and 47 per cent’ while Democrats are frustrated by the solidity of the Trump coalition, ‘a prominent feature of the political landscape for years to come’, as well as the discovery that demographic change doesn’t automatically build their permanent majority. ‘The unavoidable conclusion: unless Joe Biden’s presidency is highly successful during the next four years, the 30-year-cycle of narrow victories and regular shifts of power in the White House and the legislative branch will persist.’37

Galston, of course, doesn’t factor in the future of economic growth or the scenario of a stagnant economy with high levels of structural unemployment and poverty—a nightmare that weighed heavily upon the minds of millions of voters in early November and, as I have suggested, motivated many of them to hold their noses and cast ballots for Trump. Progressives are being realistic, not self-righteous, when they insist that profound structural change is the only programme commensurate with the needs of working people in the dark American winter that may lie ahead. But it’s the Republicans, not the Democratic factions, who will shape next year’s agenda, selecting those battlefields where they are most advantaged by their Senate majority and their lock on the Supreme Court. At the same time, Trump’s would-be successors—the current favourites include Tom Cotton, Josh Hawley, Nikki Haley and Ted Cruz—will be competing to feed red meat to the vengeful Trump faithful. With the far right running around planting traps in the path of Democrats, the lynch-mob mood amongst Republicans will become even more dangerously anti-democratic and explosive.

Last January, the well-known political scientist Larry Bartels conducted a troubling survey of Republicans. Most of them agreed that ‘the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it.’ And two-fifths believed that ‘a time will come when patriotic Americans have to take the law into their own hands.’ ‘In both cases’, Bartels adds, ‘most of the rest said they were unsure; only one in four or five disagree.’ After carefully analyzing the responses to his questionnaires, he concluded that white fear of the growing political and social power of immigrants and people of colour had acidified under Trump into a dangerous rejection of democratic norms.38 In effect, a majority of hardcore Trump supporters seem to agree with the Proud Boys and the rest of the alt-right that political violence was justified in defence of white supremacy and ‘traditional values’. States of terror are of course as American as apple pie. What was called ‘Massive Resistance’ in the late-1950s and early 1960s South involved hundreds of thousands of whites, ranging from bankers to housewives, in active opposition to the civil-rights movement, giving unabashed support to police and mob violence. Likewise one can recall the vast popularity of the nativist ‘Second’ Klan in Midwestern states like Ohio and Indiana during the 1920s. Deep structures of the past have been disinterred during Trump’s presidency and given permission to throttle the future. Civil War? Some analogy is inevitable and should not be easily dismissed.

=========

Notes at link above

No comments:

Post a Comment